On The Expiry Date Of Dreams

Getting lost in the chase. The ultimate pursuit, the pinnacle of a faultless imagination. Have you ever asked yourself the total number of dreams you have had throughout your life? Have you ever paused to ruminate on all the dreams you ever had? And what did you discover? I never really consciously thought about this. Until I sat on a patch of grass next to a Seoul subway station, iced americano sitting in the folds between my fingers, and I heard the following: 'You know, when you chase a dream, you imagine the destination as this summit you have to ascend to, you pour your all into climbing this mountain, and you imagine, that when you finally get to the top, the view must surely be incredible. So high up, there must be valleys and ridges to look down upon. But then you get there, and it is all just flat.'

Getting lost in the chase. The ultimate pursuit, the pinnacle of a faultless imagination. Have you ever asked yourself the total number of dreams you have had throughout your life? Have you ever paused to ruminate on all the dreams you ever had? And what did you discover?

I never really consciously thought about this. Until I sat on a patch of grass next to a Seoul subway station, iced americano sitting in the folds between my fingers, and I heard the following:

'You know, when you chase a dream, you imagine the destination as this summit you have to ascend to, you pour your all into climbing this mountain, and you imagine, that when you finally get to the top, the view must surely be incredible. So high up, there must be valleys and ridges to look down upon. But then you get there, and it is all just flat.'

The moment a dream expires, because you have surpassed it.

The other day I sat down and tried to think of my dreams. One of my earliest dreams being to own this giant Diddl Plush. A soft toy that, at the time, was about the same size as me. The thought of getting to fall asleep in the arms of the giant mouse decorating all the crinkled paper balls on my desk felt like the pinnacle of everything I had wanted. I still remember to this day, I was five years old, one night I dreamt of living side by side this enormous plush, and when I woke up, I was swept by an insurmountable feeling we all know: longing for something you think you can never have. Little did I know, just a few months later, for my sixth birthday, I would be picked up from school by my mother with Miss Diddl strapped into the backseat. I had reached the summit. My dream was no longer a mystical fable, it materialized through my mother's love.

At ten, my dream was for my mother to recover, for everything to fall back into peace. We, being my mother, brother and I, had just moved into a two-bedroom apartment after my mother had taken us and courageously fled the shackles of abuse. She spent the nights sleeping on the two-person couch sitting in the kitchen, while my brother and I each had a small room to ourselves. Seeing her cry became a new normal, one of the most jarring moments being when she told us in a storm of tears that maybe our lives would be easier if she was no longer alive. I wanted nothing more than for her to be okay again. To not live in fear for my mother's life. As the years passed, this dream quietly fizzled along, and although it feels faded because everything did in fact get better, it never actually disappeared. I now understand that this is because it was never truly my dream, it was a dream dreamt in her place.

When I was fourteen, my dream was to meet Ed Sheeran. A lyrical and cordial soul I so desperately latched onto during my troubled and pain-sprinkled youth. Impossible right? How could I, of all people, ever meet the most successful musical creator of the current decade? Well, you are mistaken if you think that this story goes like how teenage-fan-fantasies usually play out. I did meet Ed Sheeran, not once, but in fact, I met him twice. The only reason I met him at all being my own determination. I so desperately wanted it to become reality, that at sixteen - coming out of a long hospital stay and a near death experience, I started an online-project and sent out letters to his manager's business emails - and it worked.

When I was eighteen, my biggest dream was for Tim to live again. The countless nights I cried myself to sleep were followed by even 'countlesser' of days I woke up into with the soul-shattering realisation that he was - in fact - still dead. I did not want to live in the universe his suicide was an actual reality in. Unlike my Diddl dream, this was a dream truly unattainable, at least in the ways I wished for. No amount of yearning and longing and suffering would ever allow me to hug, kiss or touch him again.

When I was twenty-one, my dream was to travel far and wide, move abroad and swim with a humpback whale. I was so caught up in my own suffering, that the thought of floating silently alongside one of the largest creatures to ever roam this planet felt like the apex of healing. During my days of trauma therapy, I imagined myself in the water with these magical creatures countless times. However, being as disabled as I was, I thought this would never become real. I could barely leave the house or work, how was I supposed to make it to the other side of the globe on my own and swim with a 60-foot, 40-ton mammal in a far-away ocean? Surely this must be where my dreaming has reached the climax of absurdity? Oh, but I did swim with a humpback whale just two years later, after I got onto a one-way flight to Japan. And so I scaled this mountain too.

Sitting there in the Seoul summer heat, living abroad and twirling my fingers in the dirt, for the first time I reflected back on all my naive dreaming and everything it had brought me. I had lived so many of my dreams and still I felt so unaccomplished. We think of dreams as some sort of benchmark, some ultimate reality in which we reach a state of endlessly unfolding contentment. My dreams had carried me so far, so much further than I ever thought, shouldn't I feel proud? Proud for making it further than I ever thought possible? I realised then, that dreams aren't a destination, they were never meant to be. To pursue a dream is to embark on a journey. It is a migration pattern of learning, self-discovery and reinvention. The point is not to find a dream and violently chase it to the summit. The entire point of dreaming is simply the state of dreaming, the hope it carries, the fuel it brings and the emotional branching it holds. A dream is a lifeline. A lifeline, that you get to pick, no matter how irrational or absurd it may be to others. Your dream could be to become the most successful fiction writer of all time, but it could also be to sit on the floor, staring at the first book in your very own bookshelf.

So it is okay, it is okay to leave a dream behind, to start a new one or abandon it entirely when you have outgrown your last. The only point is to never stop dreaming, because it will carry you so, so, so, so far.

Reading Among Books

anything is possible here. an infinite puzzle of as and ds and ys. i grab and glue and build, but the letters are slippery. be gentle and they will stick. careful now - make them touch softly and they will turn into a harmonizing poke. a chord of somnolent notes settles into the floorboard cracks and slinks into my ears.

‘reading among books - my body weight melts off my contour and slops into the squeaking hardwood floor beneath - a nest i crawl into, a space where i sprawl my limbs and forget my body exists beyond my brain's letterbox.

anything is possible here. an infinite puzzle of as and ds and ys. i grab and glue and build, but the letters are slippery. be gentle and they will stick. careful now - make them touch softly and they will turn into a harmonizing poke. a chord of somnolent notes settles into the floorboard cracks and slinks into my ears.

the mail has arrived. i hand it back to the shelves, back to the house. i am cranial gloop in literal downtown. digesting can be so meditative, even the floorboards beneath me forget to creak.’

model: leonie buchegger

I was always a book nerd. Getting lost in books was something I took pride in. By the time I was six, I had read my first book over five hundred pages - The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

Followed by weeks of hibernating in the Harry Potter universe, at seven I got second place in a reading contest. I read on a stage in front of three hundred people. Some dormant remnant of anxiety must have made itself at home between my liver and stomach because I can recall how nervous I was to this day. Language always came easily to me, German and English classes weren't enough, no, I also had to take Italian, Spanish and Latin (extraordinarily useful) on top of that. And to spice things up, I started learning Korean in my early twenties.

Growing up in a shattered family, surrounded by abuse and lack of stability, depression slowly built itself a nest and ate up my spell of flight. My love for reading gradually started to rot away, bit by bit, alongside myself. After overcoming my troubled past, I tried picking up books time and time again, but the letters would never truly stick. Reading felt dull, not peaceful.

It wasn't until I met Joshua D.-T. in South Korea and he read to me on the Seoul metro as I dozed off on his shoulder, that the cordial notes of reading found a hidden pathway into my letterbox.

I have read twenty books since then, more than I have in the last six years combined. Weird, how people can re-open doors to dormant pieces of yourself.

So I started the new year with a book: The Midnight Library by Matt Haig.

Treewalker: Mario Dieringer

I was twenty years old when I first heard of Mario Dieringer in my local newspaper. On a Sunday morning, still deeply submerged in traumatic grief after having lost a significant other to suicide, my mother placed an odd article on the kitchen table in front of me: a man was coming to town to plant a tree and talk about surviving the unsurvivable. Trapped in mind-numbing memories, I couldn’t have imagined that this stranger’s visit would plant something in me too: a seed of hope. Years later, I would meet Mario again. We would sit in a book cafe in Berlin, I would take his portrait, and I too would have survived the unsurvivable.

A portrait of the man behind Trees of Memory

I was twenty years old when I first heard of Mario Dieringer in my local newspaper. On a Sunday morning, still deeply submerged in traumatic grief after having lost a significant other to suicide, my mother placed an odd article on the kitchen table in front of me: a man was coming to town to plant a tree and talk about surviving the unsurvivable. Trapped in mind-numbing memories, I couldn’t have imagined that this stranger’s visit would plant something in me too: a seed of hope.

Years later, I would meet Mario again. We would sit in a book cafe in Berlin, I would take his portrait, and I too would have survived the unsurvivable. His face now weathered by thousands of kilometres on foot, his eyes carrying both the weight of loss and an unmistakable spark of purpose. A German journalist who sold everything he owned, packed a custom hiking wagon with 100 kilograms of gear and set out to walk around the world with his dog Tyrion, planting dozens of trees for suicide victims along the way.

But Mario Dieringer's story doesn't begin with hope. It begins, like so many stories about transformation, in the absolute depths of despair.

Until 2011, Mario lived what appeared to be a charmed life as a TV journalist for German and international broadcasters, the perpetual optimist whose life was "basically one big celebration." No assignment was too adventurous, no journey too far-flung.

Then, at 46, he collapsed. What seemed like burnout was in actuality severe depression. Terrified by his own suicidal thoughts, he checked himself into a psychiatric facility for six months. Mario survived and rebuilt his life. He fell in love with José, who also struggled with depression but refused to get treatment. In December 2014, Mario attempted suicide and was clinically dead for five minutes before being resuscitated. José found him and saved his life. Eighteen months later, after an argument, José took his own life. "That I, of all people, would trigger his suicide will forever remain a dark shadow," Mario says.

His depression returned with crushing force. "When I had no more energy to continue," he recalls, "the thought of Trees of Memory came flying in and changed everything." The concept came to him in the shower: walk around the world and plant trees in memory of those lost to suicide. "At first, I thought I'd really lost my mind," Mario admits. "But hours later, it was clear: either you do this or you'll be dead in four weeks." In 2017, he founded Trees of Memory as a nonprofit organization, providing suicide prevention work and support for bereaved families.

That evening four years ago, when I first heard Mario speak, something inside of me shifted. I was so tormented by survivor’s guilt and regret that I thought I had been condemned to a lifetime of sorrow. I did not see a way out of the hole I was living in, and just like him, I felt haunted by the thought of death. At the end of that night, Mario pulled me in for a hug and spoke with profound sincerity and conviction: ”It will get better”.

In 2018, on the second anniversary of José's death, Mario officially begins his walk around the world. He sets out from Cologne to Frankfurt and plants the first Tree of Memory. Leaving everything behind, what remains fits into his custom-built hiking wagon: tent, sleeping gear, cooking equipment, technical equipment, batteries, clothes. One hundred kilograms total.

But he wouldn't be making this journey alone.

His four-legged friend Tyrion is a dog rescued from a Bulgarian animal shelter, a gift from friends who knew Mario needed a companion for the road ahead. Together, Mario and Tyrion set out, creating an unusual sight: a middle-aged man and his shelter dog, pulling a wagon topped with a sign reading "I'm walking around the world and planting trees of memory for suicide victims," the Trees of Memory logo displayed prominently alongside the website address.

They sleep in a tent or under the stars. Their route is determined by tree planting requests and invitations to give talks. Mario has no fixed schedule, no rigid itinerary, just an unwavering commitment to show up wherever he's needed.

Mario and Tyrion have walked almost twenty-thousand kilometres through Europe, planting over 70 trees. From Germany, the journey has expanded through Austria, Slovenia and other European countries. Each tree planting is a ceremony, often attended by the families of those being remembered. Mario doesn't just plant a tree and move on, he stays, he listens, he shares his own story. He offers something that few others can: the perspective of someone who has stood on both sides of suicide, as both a survivor of attempts and as someone bereaved by loss.

"I can explain, I can perhaps answer some of the tormenting questions that haunt those left behind and I will show that you can get back up again."

While the tree plantings form the heart of the project, Trees of Memory has expanded beyond Mario's footsteps. The organization operates "first contact points" in twelve regions across Germany, pairing bereaved families with volunteer mentors who have experienced suicide loss themselves.

Mario's journey has drawn significant media attention, appearances on German television, countless newspaper articles, over 10,000 Instagram followers tracking his progress. But the real impact lives in the people moved by Mario’s impact, people like myself.

When I met Mario in Berlin, years after that first tree planting in my town, I was struck by how the same qualities that made him gleam as a young journalist still shine through, now tempered with a groundedness, a wisdom that comes from having wandered to the darkest places the human psyche can go and finding a way back.

The journey remains a work in progress. Mario walks during warmer months, taking winter breaks to rest and plan. Each spring, he and Tyrion hit the road again, following invitations and tree requests.

For someone who once believed he had no alternative but death, Mario Dieringer has become a living embodiment of another path: transformation through purpose, healing through helping others, and the radical act of putting one foot in front of the other, even when you can't see where it leads.

One of the first things Mario said to me when he sat down across from me in that cafe in Berlin was: “You are shining, and you look so much happier”.

Somewhere along the roads of Europe, a man and his dog are walking. Behind them, a ribbon of trees. Ahead of them, thousands more kilometres to go. Beside them, invisible but present, all the people they've touched along the way, the ones still here and the ones remembered, connected by a network of roots growing deep, by the simple, profound act of planting a tree and saying: You mattered. You are not forgotten. And for those still here: keep walking.

To learn more about Trees of Memory or to request a tree, visit treesofmemory.com. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to a crisis helpline in your country. In Germany: Telefonseelsorge (0800-111 0 111 or 0800-111 0 222). You are not alone.

Callus

It doesn’t hurt anymore, the thing you did. It’s like I have grown accustomed to the pain. Like my heart has been covered in a thick layer of callus, morbid and disgusting. I wish I could peel it away.

They let me see him one final time. His skin had gone waxy and cold and his lips were discoloured in a violent shade of purple that looked nothing like sleep and everything like the end. I sat beside his body for four hours and just stared at him. A pestering compulsion to memorize every inch of his physical form like a broken printer. I wanted to take it all in and never spit it back out.

It doesn’t hurt anymore, the thing you did. It’s like I have grown accustomed to the pain. Like my heart has been covered in a thick layer of callus, morbid and disgusting. I wish I could peel it away.

I was sixteen when I learned that psychiatric wards smell like disinfectant and broken dreams. A place where you're put after attempting to end your life, white rooms with fluorescent lights that buzz perpetually and the faint resonance of someone crying through cardboard walls like mice in a paperbox.

We found each other in a sterile place where hope came in pill form and healing felt like a cruel parody acted out to keep us compliant.

That day he came on a two-hour train to keep me company in my unshowered and glacial attempt at self-loathing. Door ajar, I was stoically inspecting the loose threads of my duvet, when he silently peeked into the expired and salty cloud that was my room, carrying a hot water bottle and his gentle grin. I will never forget the way he looked at me. It was the last time I saw him alive.

The call came on a Saturday evening that marked a fault line of before and after. He was dead. The word ‘hanging’ crashed into the fragile house of cards that was my life, like a stone into a still body of water, sending ripples that would reshape every shore of my existence.

They let me see him one final time. His skin had gone waxy and cold and his lips were discoloured in a violent shade of purple that looked nothing like sleep and everything like the end. I sat beside his body for four hours and just stared at him. A pestering compulsion to memorize every inch of his physical form like a broken printer. I wanted to take it all in and never spit it back out.

What followed was six years of learning what it means to drown while standing on solid ground.

PTSD settled into my mind like a permanent resident, rearranging the furniture of my thoughts until none of them felt familiar. OCD developed as my brain’s desperate attempt to impose order on a universe that had proven itself to be fundamentally chaotic. Life became a landmine, just waiting to send my nervous system into collapse until I was left curled over toilet bowls, my body trying to expel grief that had no place else to go.

The guilt was perhaps the most agonizing part, almost methodical in its examination of every moment I had pulled away from him, every time I had chosen my own safety over his pain. It painted me as both victim and perpetrator in my own story, the person who had loved him and the person who had left him behind. I carried his death like my own personal headstone.

It was vile. I became utterly unrecognizable to myself.

There were nights when following him felt not like tragedy but like the most logical conclusion to an impossible situation. When the pain was so complete and encompassing that continuing to exist felt like the universe's most debilitating joke. Death stopped feeling like an ending and started feeling like the rightful sentence to my visceral failure.

But something stubborn in me refused to let go. Maybe it was the same part of me that had survived at sixteen, some core of defiance inside of me, nature’s unadorned instinct of survival.

My recovery was not a singular moment of breakthrough but six years of painstaking reconstruction. Six years in which I learned that trauma literally rewires your brain, but that brains are remarkably capable of being rewired again. Six years of understanding that survivor's guilt is just love with nowhere to go and that carrying someone's memory doesn't require carrying their death as punishment.

I'm twenty-four now, standing at the threshold of adult life with no degree and limited work experience, but with something more valuable than what society deems success – the bone deep knowledge that I can survive. That love, even love that ends in suicide, is worth the devastating risk and that being someone's reason for living is not a burden but a profound privilege, even when it comes wrapped in the possibility of ultimate loss.

Window Reflections

The primary coloured illumination has run its course. The silver mosaic of the disco ball is no longer dancing in an array of rainbow hues, it is now merely glistening in the dim and yellow light cast by three A23 bulbs. Or so I assume. The guy, dressed in fully white except for a black polo peeking out the edges of his cardigan, has just carried a dog-like figurine across the room. Watching the unfolding of this preparation feels like a warm blanket tucking in the slimy, cranial mess that is my mind.

There is this enormous window around fifty meters across the street. A man is walking back and forth between the pulsating flickers of a disco light, holding something that resembles the curves of a baseball bat. I don't really know what is happening behind the reflections of this awfully large pane of glass but it is hauntingly interesting to me. Maybe because it puts my mind onto a straight and easily digestible track of thoughts, some coherent baseline of stimulation that doesn't ferociously scream at me in the shape of short-form-content and bass-boosted alterations of TikTok charts.

Another guy just wheeled out a cart covered in a tangled black mess of cables which reminds me way too intensely of the extra large Venom movie posters decorating the thirty feet tall gallery of my local cinema. The figures who were so eagerly watching him up until five minutes ago have vanished behind the balding branches of a Ginkgo tree, covering a large portion of the glass front, thus diffusing this establishment's happenings into a shroud of mystery. The disco ball is going off in endless circles of primary colours, projecting an elliptical cloud of light onto the paved plaza beneath. This is the first time in a while I have felt truly peaceful. Between the mental toll of working two jobs and freelancing, I have been unintentionally depriving myself of the joy of self-expression. It's been quite a long time since I sat down like this to write, read, or paint.

I spent a large portion of my life believing that happiness is the opposition to depression. I have since come to learn that the true counterpart to this is self-expression. It is basic human need as much as is hydration or movement. She who does not have the space nor the ability to express herself will wither like daffodils in their inability to stretch petals toward missing rays of sunlight on a cloudy day.

The primary coloured illumination has run its course. The silver mosaic of the disco ball is no longer dancing in an array of rainbow hues, it is now merely glistening in the dim and yellow light cast by three A23 bulbs. Or so I assume. The guy, dressed in fully white except for a black polo peeking out the edges of his cardigan, has just carried a dog-like figurine across the room. Watching the unfolding of this preparation feels like a warm blanket tucking in the slimy, cranial mess that is my mind.

Maybe the world would be a better place if more people sat down across window panes.

We live in a society powered by the incoherent identification with achievement, which leaves little room for focusing inward to bring the intrinsic outward, it instead teaches to take what is outward and let it root inward. It robs us of genuine expression and seeks to depress the internal with external stimuli. There is this German saying 'Hast du was, bist du was!' which roughly translates to "If you have something, you are something!"

We constantly strive to possess - job titles, certificates, perceptions of others, the need to be meaningful, to have 'meaningful', to do meaningful. A cultural epidemic that even I have become patient of. Don't get me wrong - it's not a bad thing to wish for a life with meaning, purpose and remembrance. But when has this meaning turned into the need to be grand and known?

Why can helping a snail across the road not be as meaningful?

When did we let others decide what has meaning and what does not?

Shouldn't I be the one dictating grandness in the scale of my own life?

I haven't seen the guy in at least 10 minutes. It might be time to go home.

Visual Journey through South Korea

I was recently given the wonderful opportunity to join Antje from @nextstopkorea and Dony from @BusanMate on an unforgettable journey through South Korea, capturing their adventures through my lens. What followed was a week of discovery, tradition and natural wonder that exceeded all my expectations.

I was recently given the wonderful opportunity to join Antje from @nextstopkorea and Dony from @BusanMate on an unforgettable journey through South Korea, capturing their adventures through my lens. What followed was a week of discovery, tradition and natural wonder that exceeded all my expectations.

Jeonju (전주): Where Tradition Comes Alive

Our adventure began in Jeonju, a city where history whispers from every corner. We dove straight into the culinary heart of Korea, savoring authentic Jeonju Bibimbap (전주 비빔밥) at its birthplace. This iconic dish, a harmonious bowl of rice, vegetables and gochujang (고추장, red chili paste), has evolved through Korean dynasties, with Jeonju often quoted as its home.

Wandering through Jeonju Hanok Village (전주 한옥마을) felt like stepping back in time. Traditional wooden houses with their elegantly curved roofs lined the streets and as evening fell, we experienced true Korean hospitality by spending the night on warm ondol (온돌, underfloor heating) floors in a traditional hanok (한옥, traditional Korean house).

Mokpo (목포) to Jeju (제주): Ferry Adventure

Our journey continued south to Mokpo, where we boarded a ferry bound for Jeju Island. Despite the overcast skies and steady rain, our spirits remained high. Upon arrival, we warmed ourselves with Jeju's signature Abalone Hot Stone Pot Rice (전복돌솥밥, jeonbok dolsot-bap), a bubbling comfort that perfectly captured the island's maritime character.

Meeting the Haenyeo (해녀): Women of the Sea

The following day was one of my personal highlights. At Haenyeo's Kitchen in Bukchon (북촌), we got to eat freshly made meals with locally harvested ingredients traditionally collected by Haenyeo - Jeju's legendary sea women. These incredible women have been free diving these waters for generations, some still diving well into their 90s. They harvest marine life like abalone, sea urchin and seaweed from the ocean floor without any breathing equipment.

Getting to learn about their culture and way of life through both their words and their food was humbling and left me with a deep sense of respect for their heritage.

Jeju's Natural Wonders

One of our most exciting stops was Jeongbang Waterfall (정방폭포), where three waterfalls drop straight into the ocean. Standing on the volcanic rocks with the group posing for photos, we could feel the raw power of the water and sea spray around us.

Bijarim Forest (비자림) was like stepping into another world. Walking among nutmeg trees (비자나무, bijanamu) that are hundreds, some even over a thousand years old, felt surreal. Sunlight came through the dense canopy, creating rays of light that danced through the afternoon mist. The forest floor was soft with moss and the air smelled of earth and ancient wood. This protected forest has stood here for centuries.

At Sangumburi Crater (산굼부리), we stood at the edge of a huge volcanic formation, looking down into the bowl-shaped depression below. Unlike most craters, Sangumburi has no peak - just a perfectly round hollow formed by a volcanic explosion thousands of years ago. The crater floor has a unique mix of rare plants and trees, creating beautiful layers of green that change with the seasons.

We took a quick ferry ride to Udo Island (우도), a small island off Jeju's eastern coast. Standing at the edge near Udobong Peak (우도봉), the dramatic rock formations jutting out of the turquoise water were incredible. The four tiny figures in our photo really show how massive these rock formations are!

Sweet Surprises: Green Tangerine Picking

One of the most delightful experiences was visiting a local tangerine orchard. Despite their vibrant green color, Jeju's green tangerines (풋귤, pootgyul) are incredibly sweet and juicy, a revelation for anyone accustomed to thinking green means unripe. We met a local farmer who generously shared his knowledge about cultivating these unique citrus fruits in Jeju's volcanic soil. The taste of a freshly picked tangerine, still warm from the sun, is something I won't soon forget.

서귀다원 Green Tea Fields

The rolling green tea fields of a local family-owned farm stretched before us like an ocean. Walking between the meticulously maintained rows, populated by hundreds of dragonflies, was like straight out of a fairytale. The green tea (녹차, nokcha) we tried here was one of the best green teas I have ever had!

Jeju Folk Village (제주민속촌): Wishes and Traditions

At Jeju Folk Village, we got to see what life on Jeju looked like in the past. This outdoor museum has authentic thatched-roof houses and shows traditional Jeju culture. We took part in traditional wish-making, something that has connected generations of Jeju residents to their ancestors. The ancient dol hareubang (돌하르방, stone grandfather statues) are scattered throughout, they have been protecting Jeju homes for centuries and you see them everywhere on the island.

Bonte Museum (본태박물관): Art Meets Nature

On our last day we visited Bonte Museum, a nice quiet break from all the outdoor activities. This art museum combines modern architecture with Jeju's natural surroundings and has collections of Buddhist art, Traditional Korean art and contemporary pieces. The wooden sculptures and colorful painted figures were beautiful and showed centuries of artistic tradition.

Reflections

This journey through South Korea was more than just a photography assignment, it was an immersion into a culture that honors its past while embracing the future. From the Haenyeo's century-old diving traditions to the modern wind farms powering Jeju's future, from ancient nutmeg forests to contemporary museums, every moment revealed another layer of Korea's rich tapestry.

Traveling with Antje and Dony and meeting the wonderful people along the way reminded me why I love photography. It's not just about capturing beautiful landscapes or interesting faces, it's about preserving moments and building bridges between cultures.

South Korea, with its warmth, beauty and endless surprises, has captured my heart.

All photographs © Nomi Sophie

Mercy Street, Dreamer’s Alley

Just a few weeks ago I walked by a pretty dilapidated building in Seoul. A place where someone's dream has quite obviously ended, where the vision that brought something into existence has moved on, failed or simply run its course. But it lingers on, the walls still stand and the rooms still hold space. The architecture of someone's hope remains long after the dreamer has gone.

Dreaming and persevering are the same thing, just different words for the stubborn human insistence on making something from nothing and refusing to let the imagined remain imaginary.

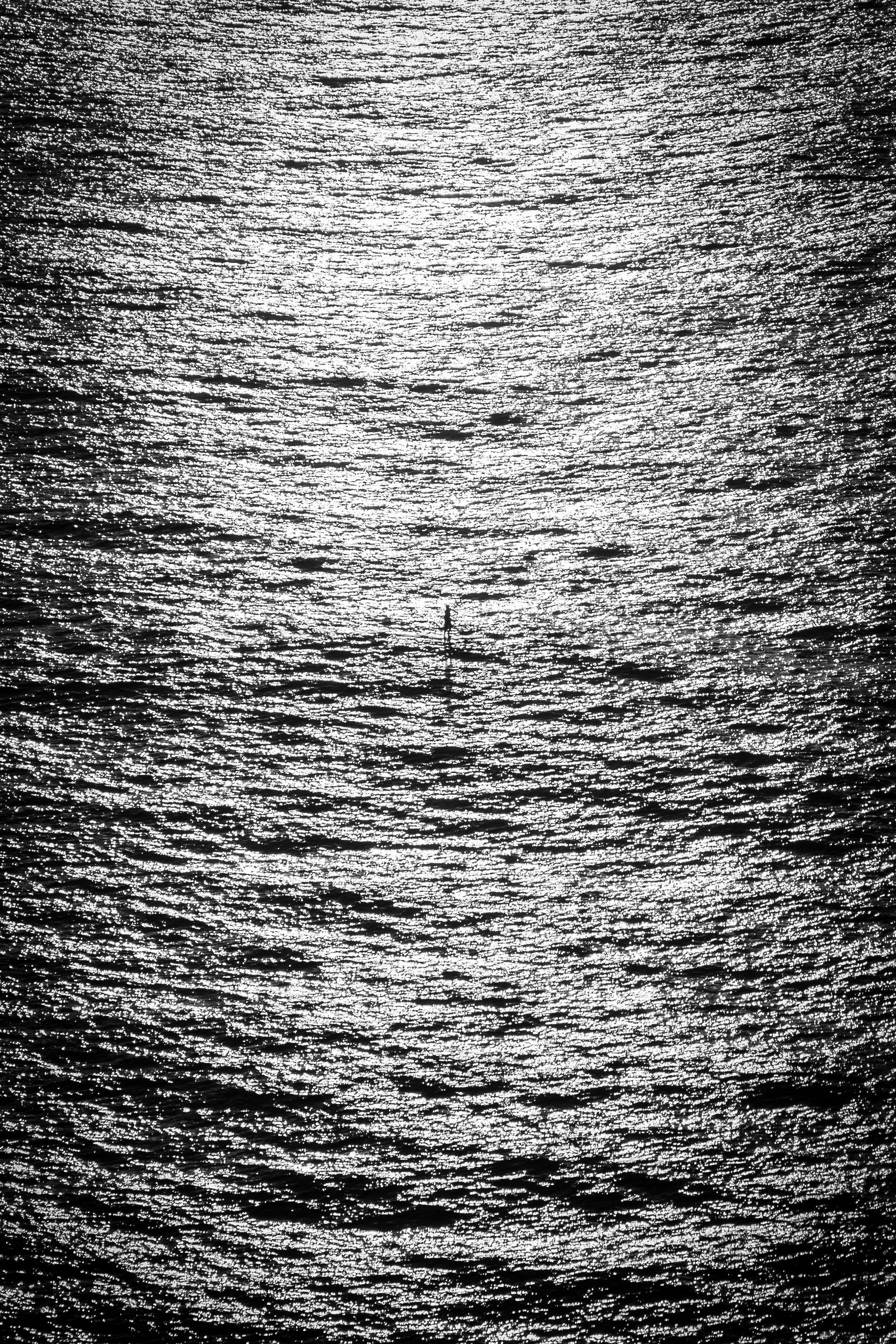

elderly man looking out at sea - jeju, south korea

Just a few weeks ago I walked by a pretty dilapidated building in Seoul. A place where someone's dream has quite obviously ended, where the vision that brought something into existence has moved on, failed or simply run its course. But it lingers on, the walls still stand and the rooms still hold space. The architecture of someone's hope remains long after the dreamer has gone.

There is a song by Peter Gabriel I really enjoy that reminds me of this liminal notion. I think at this point I have shared ‘Mercy Street’ with at least two dozens of people and every time someone asks, I tell them the same thing: to dream is to persevere. If you are looking for the connection between my conclusion and his piece of art I recommend to take a quiet listen and let yourself be embraced. The fundamentals of this song explore the idea of survival amidst tremendous despair, inspired by poet Anne Sexton, and how everything we are surrounded by, was, in its humble beginnings, just a wishful thought in someone's head.

The song speaks of how all buildings, all cars, were once just dreams. I think about that part of the song quite often whenever I stroll through randomly chosen side alleys with my camera, examining raw and quiet spaces of everyday life. Some empty parking garage at dusk. The worn steps of an apartment building where thousands of feet have traced the same path. A single window glowing in an otherwise dark building. Shattered glass below a curb.

These aren't remarkable things. But they're evidence of persistence. Someone imagined that parking garage. Drew it. Poured concrete. Built something from nothing because they needed it to exist. That's what dreaming is, not just the pretty, aspirational version we talk about at graduations but also the stubborn insistence on bringing something into the world that wasn't there before.

As a photographer I'm drawn to these monuments of quiet perseverance. A corner store that's been run by the same family for thirty years. The handwritten sign taped to a door. The chair someone left on a curb, still perfectly functional, just no longer needed. Each one represents someone's dream made tangible, even if that dream was as simple as "I need somewhere to sit" or "people need groceries in this neighborhood."

Gabriel's song understands something about survival that took me a long time to learn: that continuing to exist in the face of despair is itself an act of creation. That waking up and putting on my clothes when everything feels impossible is its own form of dreaming, the dream that today might be bearable and that tomorrow might be different.

That's what the song means to me. To dream isn't about the destination. It's about the perseverance of bringing something from the abstract into the real. Of saying "this could exist" and then doing the unglamorous work of making it exist. Of drawing light from the simple ability of imagining something that has not yet come to fruition.

Every photograph I take is my own version of this. A moment that existed only in my mind's eye until I directed my camera at something and pressed the shutter. A way of seeing that I am trying to make real, trying to share and trying to preserve against the inevitable forgetting that comes with time.

Dreaming and persevering are the same thing, just different words for the stubborn human insistence on making something from nothing and refusing to let the imagined remain imaginary.

Buildings don't announce themselves. Cars rust without attendance. But they were all just someone's small or large act of faith that what they imagined could become real. And now here they stand, holding space in the world and show us that perseverance looks like this: solid and unglamorous.

This is why I photograph. Every dream that becomes real is proof that we can survive our despair long enough to make something that outlasts it.

Between Armrest and Atmosphere

I write this as I sit perched between armrests inside a giant tin can - a giant tin can with wings. A tin can that is supposed to carry me over the Philippine Sea from Sydney to Shanghai.

The clock on the rectangular screen in front of me reads five hours and eighteen minutes. Time moves thick and heavy in this floating-real-world time capsule. Like the Elmer's glue that I would sink my hands into in my childhood days. Enough minutes and seconds to think about quite literally every minute and second of the past six months.

I write this as I sit perched between armrests inside a giant tin can - a giant tin can with wings. A tin can that is supposed to carry me over the Philippine Sea from Sydney to Shanghai.

The clock on the rectangular screen in front of me reads five hours and eighteen minutes. Time moves thick and heavy in this floating-real-world time capsule. Like the Elmer's glue that I would sink my hands into in my childhood days. Enough minutes and seconds to think about quite literally every minute and second of the past six months.

As we drift apath to the Philippine archipelago Shanghai grows closer, steadily and excruciatingly slow. "Shanghai is not far from Korea" I think, as my gaze glides across the lit up screen.

South Korea, a place that has witnessed me transform into a version of myself which had long been buried underneath piles of rubble and ash, left behind by the cataclysms of my youth.

As I sit squished between two strangers, who, for some reason, are also embarking upon this gum-stretching journey to Shanghai from Oceania on a random Thursday at eleven in the morning, I find myself reminiscing moments which felt so vivid I wish I could download their atmosphere onto a hard drive in my brain to immortalize their still flickering bliss.

Many of these moments on my journey involved me looking up at the moon. Or the sun. Or a bug. And the other half involved people.

Sharing a boiling meal out of one bubbly pot with the family you made in a foreign country. A passerby offering you their umbrella in the rain. Giggling with the guy you met at an art gallery as you leap mid air during a silent disco. Being gifted free food to try as you eat alone in a basement restaurant. Spinning ten times before you throw off a frisbee to the strangers who just turned friends. Running up a mountain trek at 4am with someone you met a week ago. A dwarfish man helping you retrieve your bag charms from within a bench in front of a bookstore you just spent your entire afternoon reading in. Screaming along to "I Want to Know What Love Is" as you and your friends stick your fingers into the piercing airflow outside the Toyota Yaris you just rented for the day. Sharing hands with your newly acquired friend from Japan, your left arm squeamishly flopping behind your head, as you lunge into the paralyzing cold of an Australian waterfall in winter. Helping the friend whom you just made after swimming with whales pull off their wetsuit in the middle of a parking lot. Being pulled in for a saw-dusty group hug in between cracked and chopped trees as ants draw circles on your shoecaps. Laughing until you choke as your new hiking buddy mumbles out of sheer exhaustion. Staring at iridescent jellyfish dancing weightlessly while you hold hands with someone who makes you feel at home in a place that you are not.

I could probably fill ten more pages with moments like these. They collect in my chest like pressed flowers in a herbarium. It's the kind of moments that make you pause months later, overwhelmed with the amount of chest-hollowing beauty you were allowed to experience. How much connection you stumbled into.

Isn't it beautiful how our lives are essentially an endless stack of expansive memories like these? How throughout our - in context - pretty short visit on this blue bulbous sphere we call home, we all build a museum of intricate wonders uniquely our own? It could be the way light falls perfectly on a leaf in the dawn of day or the taste of thick humid evening air as you strut home after having said goodbye to someone who inspired you. Essence that can't be quite captured or shared. Something that thrives in the margins between memory and feeling.

I gently tap on the illuminated plastic in front of me. The time reads four hours and twenty-five minutes.

The Biological Lense

They say the eyes are windows to the soul but I think they're something even more extraordinary, they are each a unique camera that has never existed before and will never exist again. Every iris is a one-of-a-kind aperture, every pupil dilates to let in light that will be processed by a mind unlike any other in history.

When you photograph eyes in macro detail you are not just capturing anatomy. You are documenting the very instruments through which entire universes of experiences are filtered. These are the lenses that have watched sunrises that moved someone to tears, that have seen loved ones' faces light up with joy, that have witnessed moments of heartbreak no one else will ever know.

They say the eyes are windows to the soul but I think they're something even more extraordinary, they are each a unique camera that has never existed before and will never exist again. Every iris is a one-of-a-kind aperture, every pupil dilates to let in light that will be processed by a mind unlike any other in history.

When you photograph eyes in macro detail you are not just capturing anatomy. You are documenting the very instruments through which entire universes of experiences are filtered. These are the lenses that have watched sunrises that moved someone to tears, that have seen loved ones pass away, that have witnessed moments of heartbreak no one else will ever know.

That brown eye flecked with gold? It belongs to someone who sees spring differently than you do. Those long lashes have blinked away tears of anguish and detriment you have no idea about. That particular shade of green in my mother’s eyes has reflected trees and skies from a childhood spent in places most could not imagine today.

There's something about the way children encounter the world that adults spend decades trying to remember. They haven't yet learned to dismiss the ordinary as unworthy of attention. A puddle becomes an ocean, shadows on walls transform into dancing creatures and the sound of wind through leaves carries conversations from invisible friends.

My best friend’s chestnut tinted eyes reveal someone who collects moments most people discard - the precise way a pigeon lifts her foot as it struts along a paved road, or how the multicoloured bead-curtain on her neighbour’s window reminds her of pastel candy necklaces. Her irises hold copper threads that seem to catch light like coiled wire in mercury bulbs.

The blue eyes that carry a certain melancholy see beauty in places others find unsettling. They're drawn to the shadows between streetlights, the way faces distort in subway car windows, how music venues look empty after everyone has gone home. There's something about sadness that sharpens vision - these eyes catch the loneliness in Edward Munch's ‘The Scream’ and find kinship in the rawness of live concerts where strangers scream lyrics together in the dark.

My mother's eyes carry the strangest gift: they've accumulated decades of experience yet somehow gotten more curious, not less. The golden flecks in her hazel irises seem to multiply each year, as if wonder itself is sedimentary, building up in layers. She still giggles at sunsets, still finds non-animals in cloud formations with the dedication of a professional zoologist.

Each pair does the same impossible work: transforming light into stories - the same way children turn pieces of trashed cardboard into rocketships to embark on lunar expeditions atop blotchy and tattered living room carpets.

Every macro shot reveals intricate landscapes. Irises aren't just colored circles - they're topographical maps with valleys and ridges, patterns as unique as fingerprints. Some look like abstract paintings while others resemble aerial views of river deltas or dried earth.

But it's the stories behind each individual lense that fascinate me most. These eyes have been the first things lovers saw in the morning. They've watched children take first steps, witnessed final breaths, seen sunsets from hospital windows and city skylines from airplane seats. They've cried over books, sparkled with inside jokes and rolled with teenage vexations. Each eye is an archive of moments, not just what was seen, but how it was seen. The same sunset looks different through eyes clouded in grief versus eyes bright with new love.

What moves me the most is realizing that these eyes will never see themselves the way I see them through my lens. They can glimpse their reflection in mirrors and see themselves in photographs but they'll never experience their own gaze from the outside. They'll never see how their pupils contract in bright light or how their expression shifts when they're lost in thought.

We spend our entire lives looking out through these windows but we can never truly see the windows themselves.

It's the ultimate blind spot - we use our eyes to see everything except our own seeing.

When I show people macro photographs of their own eyes, there's always a moment of startled recognition followed by something deeper, some kind of wonder at the strangeness of being housed inside a body, of experiencing the world through this peculiar biological camera.

Now show the same photograph to different people and watch their eyes while they look at eyes. My mother sees storm clouds brewing in brown irises. My coworker insists they can see unicorns galloping through golden flecks and my friend Elo, the one enamoured by the way pigeons wobble their heads as they pace, she looks at hazel eyes and sees forests where each color change marks a different season, a green ocean where deer made of light particles leap between shades of amber and green.

Every eye tells me that there are as many worlds as there are ways of seeing. The child seeing monsters in pupils and cookies in corneas, my friend discovering beauty in places others call ugly - they're all right. They're all seeing truly, just differently.

In our age of division and misunderstanding, we need to remember that we're all just doing our best to make sense of reality through our own unique apertures. The same light hits all our retinas but the stories we create from it - unicorns and storm clouds and sleeping monsters - those are entirely our own.

The next time someone sees the world differently than you do, remember: they're not wrong. They're just looking through a different camera, one shaped by experiences you'll never have, calibrated by a consciousness you'll never fully understand.

And that's not an error in the system of being human, it's the most beautiful feature of it all.