Callus

It doesn’t hurt anymore, the thing you did. It’s like I have grown accustomed to the pain. Like my heart has been covered in a thick layer of callus, morbid and disgusting. I wish I could peel it away.

I was sixteen when I learned that psychiatric wards smell like disinfectant and broken dreams. A place where you're put after attempting to end your life, white rooms with fluorescent lights that buzz perpetually and the faint resonance of someone crying through cardboard walls like mice in a paperbox.

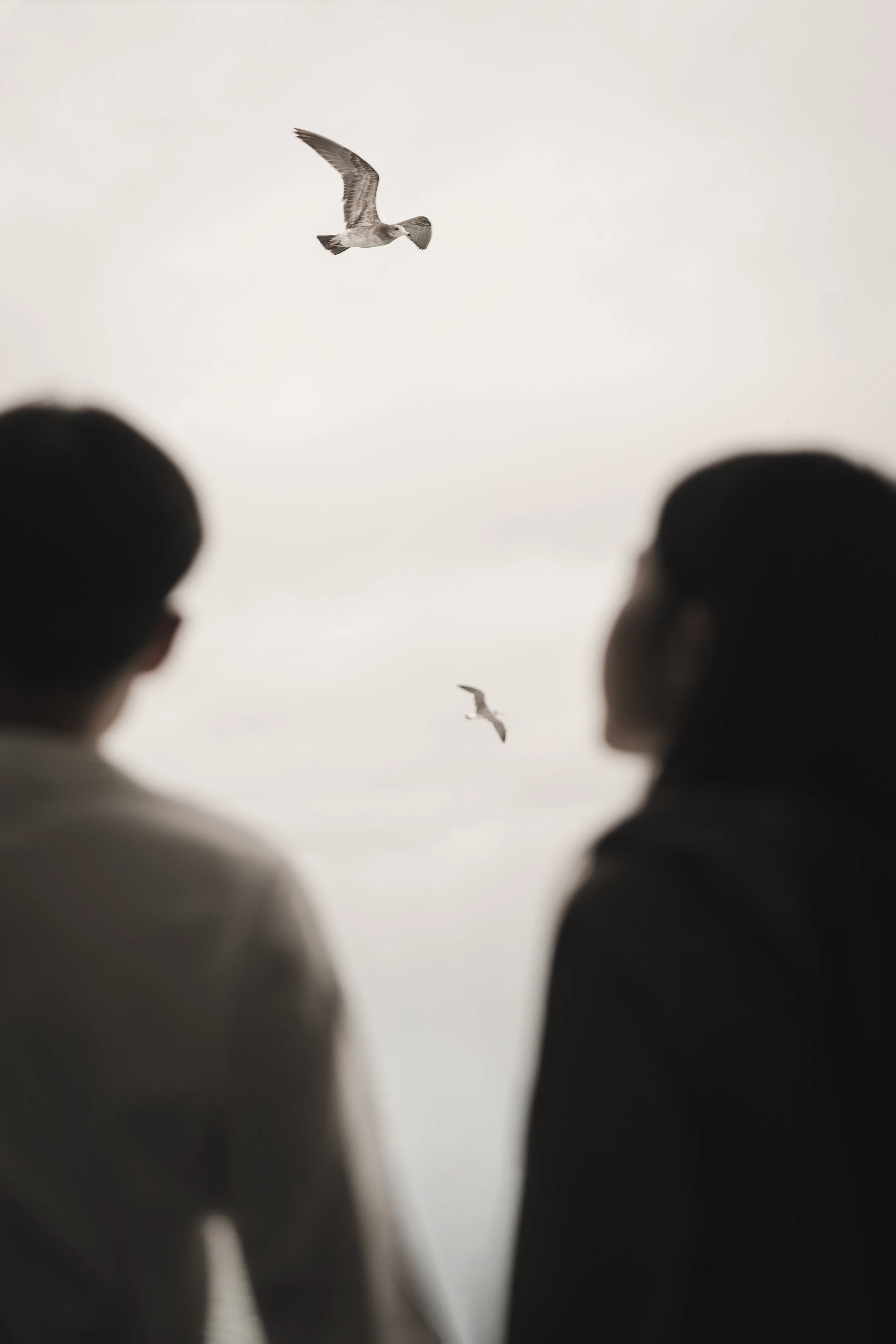

We found each other in a sterile place where hope came in pill form and healing felt like a cruel parody acted out to keep us compliant.

That day he came on a two-hour train to keep me company in my unshowered and glacial attempt at self-loathing. Door ajar, I was stoically inspecting the loose threads of my duvet, when he silently peeked into the expired and salty cloud that was my room, carrying a hot water bottle and his gentle grin. I will never forget the way he looked at me. It was the last time I saw him alive.

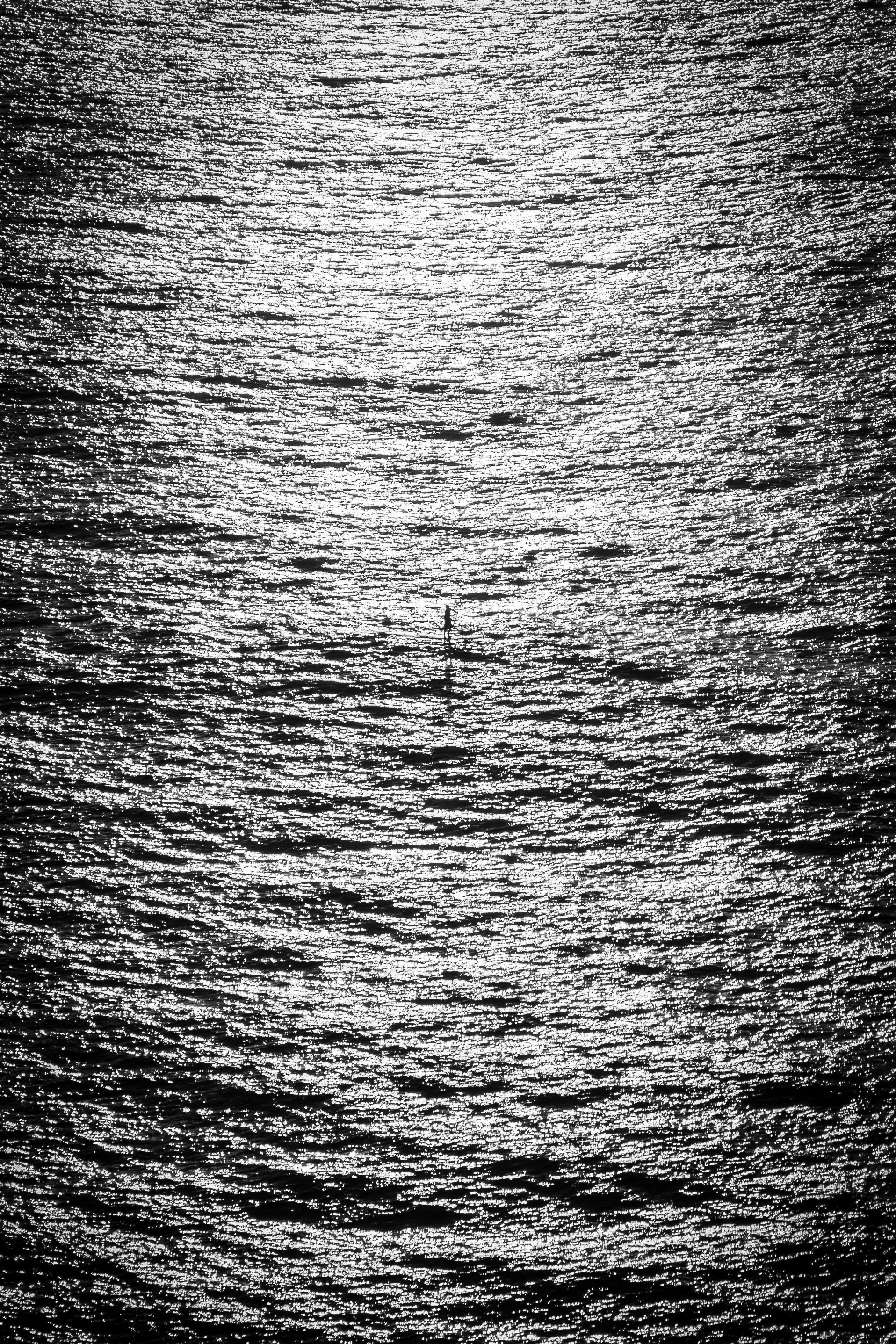

The call came on a Saturday evening that marked a fault line of before and after. He was dead. The word ‘hanging’ crashed into the fragile house of cards that was my life, like a stone into a still body of water, sending ripples that would reshape every shore of my existence.

They let me see him one final time. His skin had gone waxy and cold and his lips were discoloured in a violent shade of purple that looked nothing like sleep and everything like the end. I sat beside his body for four hours and just stared at him. A pestering compulsion to memorize every inch of his physical form like a broken printer. I wanted to take it all in and never spit it back out.

What followed was six years of learning what it means to drown while standing on solid ground.

PTSD settled into my mind like a permanent resident, rearranging the furniture of my thoughts until none of them felt familiar. OCD developed as my brain’s desperate attempt to impose order on a universe that had proven itself to be fundamentally chaotic. Life became a landmine, just waiting to send my nervous system into collapse until I was left curled over toilet bowls, my body trying to expel grief that had no place else to go.

The guilt was perhaps the most agonizing part, almost methodical in its examination of every moment I had pulled away from him, every time I had chosen my own safety over his pain. It painted me as both victim and perpetrator in my own story, the person who had loved him and the person who had left him behind. I carried his death like my own personal headstone.

It was vile. I became utterly unrecognizable to myself.

There were nights when following him felt not like tragedy but like the most logical conclusion to an impossible situation. When the pain was so complete and encompassing that continuing to exist felt like the universe's most debilitating joke. Death stopped feeling like an ending and started feeling like the rightful sentence to my visceral failure.

But something stubborn in me refused to let go. Maybe it was the same part of me that had survived at sixteen, some core of defiance inside of me, nature’s unadorned instinct of survival.

My recovery was not a singular moment of breakthrough but six years of painstaking reconstruction. Six years in which I learned that trauma literally rewires your brain, but that brains are remarkably capable of being rewired again. Six years of understanding that survivor's guilt is just love with nowhere to go and that carrying someone's memory doesn't require carrying their death as punishment.

I'm twenty-four now, standing at the threshold of adult life with no degree and limited work experience, but with something more valuable than what society deems success – the bone deep knowledge that I can survive. That love, even love that ends in suicide, is worth the devastating risk and that being someone's reason for living is not a burden but a profound privilege, even when it comes wrapped in the possibility of ultimate loss.